Abstract

β2 subunit containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (β2*nAChRs; asterisk (*) denotes assembly with other subunits) are critical for nicotine self-administration and nicotine-associated dopamine (DA) release that supports nicotine reinforcement. The α6 subunit assembles with β2 on DA neurons where α6β2*nAChRs regulate nicotine-stimulated DA release at neuron terminals. Using local infusion of α-conotoxin MII (α-CTX MII), an antagonist with selectivity for α6β2*nAChRs, the purpose of these experiments was to determine if α6β2*nAChRs in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell are required for motivation to self-administer nicotine. Long-Evans rats lever-pressed for 0.03 mg/kg, i.v., nicotine accompanied by light+tone cues (NIC) or for light+tone cues unaccompanied by nicotine (CUEonly). Following extensive training, animals were tested under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule that required an increasing number of lever presses for each nicotine infusion and/or cue delivery. Immediately before each PR session, rats received microinfusions of α-CTX MII (0, 1, 5, or 10 pmol per side) into the NAc shell or the overlying anterior cingulate cortex. α-CTX MII dose dependently decreased break points and number of infusions earned by NIC rats following infusion into the NAc shell but not the anterior cingulate cortex. Concentrations of α-CTX MII that were capable of attenuating nicotine self-administration did not disrupt locomotor activity. There was no effect of infusion on lever pressing in CUEonly animals and NAc infusion α-CTX MII did not affect locomotor activity in an open field. These data suggest that α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell regulate motivational aspects of nicotine reinforcement but not nicotine-associated locomotor activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in developed countries and is a growing health problem worldwide (WHO, 2008). Nicotine, the major psychoactive ingredient in tobacco, and cigarette-associated cues result in mesolimblic dopamine (DA) release from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and activation of VTA projection regions including the anterior cingulate cortex and the nucleus accumbens (NAc), brain areas associated with the rewarding effects of nicotine in smokers (Stein et al, 1998; Schroeder et al, 2001; Due et al, 2002; Volkow et al, 2007). Lesions of DA projections to the NAc attenuate nicotine self-administration (Corrigall et al, 1992), suggesting that these DA inputs are critical for nicotine reinforcement.

An accumulation of transgenic and neurochemical data suggests that nicotine-associated DA release and nicotine reinforcement are regulated by nicotinic receptors that contain the β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (β2*nAChR; asterisk (*) denotes assembly with other subunits) (Corrigall et al, 1994; Picciotto et al, 1998; Champtiaux et al, 2003; Salminen et al, 2004, 2007; Tapper et al, 2004; Maskos et al, 2005; Drenan et al, 2008; Pons et al, 2008), making these receptors an attractive therapeutic target for tobacco cessation (Gonzales et al, 2006; Rollema et al, 2007). β2*nAChRs, however, have a ubiquitous expression pattern and contribute more generally to motivation, mood, and cognition (for review, see Levin et al, 2006; Brunzell and Picciotto, 2009). Because β2*nAChRs are also very diverse in their composition, identification of receptor subunits that assemble with β2 but that have a more selective expression pattern may lead to tobacco cessation compounds with less potential for side effects.

The α6 nAChR subunit assembles with β2 but is selectively expressed in catecholaminergic nuclei and on terminals in catecholaminergic projection areas (Le Novere et al, 1996; Klink et al, 2001). β2*nAChRs can be classified according to their sensitivity to the cone snail toxin, α-conotoxin MII (α-CTX MII). Synaptosome studies using a combination of knockout technology and nicotinic antagonism with the α-CTX MII peptide indicate that α6β2*nAChRs on striatal DA terminals participate in nicotine-stimulated DA release (Champtiaux et al, 2003; Salminen et al, 2004, 2007). Both α3β2* and α6β2* nAChRs are highly sensitive to α-CTX MII antagonism (Cartier et al, 1996; Kuryatov et al, 2000; McIntosh et al, 2004), but expression of the α6 subunit greatly predominates in the VTA and NAc, where the α3 subunit is essentially absent (Champtiaux et al, 2002; Whiteaker et al, 2002; Salminen et al, 2005).

A recent report by Drenan et al (2008) showed that a single-point mutation in the pore-forming region of the α6 subunit, which renders α6β2*nAChRs hypersensitive to nicotine, led to nicotine-associated stimulation of VTA DA neurons and locomotor activation at otherwise subthreshold levels of nicotine; these data suggest that activation of α6β2*nAChRs are sufficient for DA-stimulating effects of nicotine. In addition, nicotine self-administration is absent in α6 subunit null mutant mice but lentiviral rescue of α6 subunit mRNA in the VTA region of these animals leads to recovery of nicotine self-administration in an acute, single-day, tail-vein procedure (Pons et al, 2008). Together these studies suggest that α6β2*nAChRs on mesolimblic DA neurons regulate DA release and nicotine reward; however, the neuroanatomical locus where α6β2*nAChRs exert their effects on nicotine reinforcement and locomotor activation is unclear. In addition, although the tail-vein self-administration paradigm suggests that α6β2*nAChRs in the VTA and/or VTA projection areas may be critical for initiation of tobacco use, less is known regarding the role of these receptors in nicotine reinforcement following repeated nicotine exposure. The current studies used a more sustained nicotine self-administration paradigm in rats. Following training under a fixed ratio (FR) schedule of reinforcement, animals were switched to a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement in which rats were required to emit an increasing number of responses for a single i.v. infusion of nicotine accompanied by light and tone cues (NIC). To determine if MII-sensitive nAChRs on terminals in the NAc shell and anterior cingulate cortex regulate motivation for nicotine and nicotine-associated cues, we used local infusions of α-CTX MII to block α6β2*nAChRs in these DA projection areas immediately before PR testing. Control animals lever-pressed for the same cues as nicotine subjects, but the cues were unaccompanied by nicotine (CUEonly). Infusion of α-CTX MII into the NAc shell, but not the anterior cingulate cortex, significantly reduced lever pressing of NIC animals without affecting responding of CUEonly rats. Concentrations of α-CTX MII that impaired nicotine self-administration also had no effect on locomotor activity in the open field, suggesting that α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell selectively regulate motivation for nicotine reinforcement or for conditioned reinforcers associated with nicotine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Twenty-eight adult, male, Long-Evans rats (Harlan Laboratories, Dublin, VA), weighing approximately 300 g on arrival, were used for these studies. Rats were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 0600 hours). Animals began testing at 320 g; animals were nutritionally maintained at this body weight by daily food rations throughout behavioral testing (Christian et al, 1998). The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Commonwealth University, and all animals were treated according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as set forth by the National Institutes of Health.

Drug Dosing and Administration

During self-administration procedures, rats received 0.03 mg/kg, i.v., infusion of nicotine (by weight of freebase) in 0.0533 ml delivered over 1 s. Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and stored in the dark to prevent degradation. α-CTX MII was synthesized as previously described (Cartier et al, 1996) and dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline. Aliquots were stored at −20°C until used for experimentation and were kept at 4°C no longer than 1 week after thawing. Animals received 0.5–1 μl intra-accumbens shell infusions of 0, 1, 5, or 10 pmol per side of α-CTX MII. For locomotor studies, rats received s.c. injections of 0.175 mg/kg nicotine (by weight of freebase) at a concentration of 2.0 mg/ml in sterile saline.

Intra-Jugular Catheter Implantation

All surgeries were performed using aseptic procedures. Anesthesia was induced with 3.5% isoflurane gas at 3.5 liter/min oxygen and maintained at 2.0% isoflurane and 2.5 liter/min of oxygen. Surgical areas were shaved and cleaned with 7.5% povidone–iodine and 70% reagent alcohol. A tapered polyurethane catheter (3.5 French; Access Technologies) was implanted in the right jugular vein above the atrium. Following implantation, the catheter was passed subcutaneously to the rat's back and connected to a back-mounted pedestal (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA). To prevent infection, all rats received s.c. injection of 75 000 U penicillin G and 0.1 ml intracatheter injection of 0.031 mg/ml ticarcillin/clavulanate in 25% glycerol/heparinized saline (catheter lock). During surgery, rats received 5 mg/kg, i.p., carprofen for preemptive analgesia. Rats also received 64 mg acetaminophen mixed in wet chow for 3 days following surgery and were allowed to recover for at least 5 days before self-administration training. Before and after training sessions, catheters were irrigated with 0.1 ml heparinized saline (5 USP units per ml heparin). After post-session flushing, animals received 0.1 ml of the catheter lock. Catheter patency was determined as a rapid loss of balance following 1.6 mg, i.v., ketamine injection. In the case of catheter failure, the left jugular vein was catheterized and the animal was returned to the study.

Intracranial Guide Cannula Implantations

Animals were anesthetized, prepared for surgery, and received postoperative care as described above. Rats were placed in a stereotaxic device with bregma and lambda leveled to within 0.05 mm. Each animal was implanted with a 22-gauge bilateral guide cannula (Plastics One) targeting the NAc shell (+1.6 mm anterior, ±0.75 mm from midline, −6.5 mm ventral from bregma) or anterior cingulate cortex (+1.8 anterior, ±0.75 from midline, −2.75 ventral from bregma). Guide cannulae were held in place with dental cement anchored with jeweler's screws. Dummy cannulae were inserted into the guides to maintain patency. Following behavioral procedures, brains were harvested to assess cannulae placement.

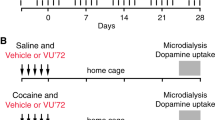

Nicotine Self-Administration

All self-administration procedures occurred in operant chambers located within sound-attenuating boxes (MED Associates, St Albans, VT). Rats were placed in experimental chambers at the beginning of each 2-h self-administration session and attached through an implanted pedestal to stainless-steel-encased infusion tubing suspended from the chamber ceiling (Plastics One). These tethers enabled rats to move freely about the chamber during training and testing. Levers were extended and a 5 W houselight remained illuminated during all behavioral testing. Rats were reinforced under a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement followed by a 20 s timeout period. Nicotine infusions were delivered through a Model PHS-100 syringe pump located on the outside each sound-attenuating box. A panel light above the active (right-side) lever and a Sonalert tone generator at the rear of the chamber operated as cues. For NIC rats (n=12), depression of the active lever resulted in delivery of a 1 s, 0.03 mg/kg, i.v., nicotine bolus and a 20 s light+tone cue. To control for potential locomotor depressant effects of the α-CTX MII and for effects of conotoxin on the primary reinforcing properties of the cues, a separate group of rats received the same cues without nicotine infusion upon depression of the active lever (CUEonly, n=7). The left lever was designated as inactive; depressions of this lever were without scheduled consequences. Rats were trained for at least 12 days and to criterion of 3 consecutive days of >70% accuracy as measured by the ratio of active/total (left+right) lever presses. Animals that received cannula implantation after training received a refresher session under FR1 conditions before PR training. Behavioral programs and data collection were controlled by MED-PC IV software (MED Associates).

Progressive Ratio Responding Maintained by Nicotine

Following FR training, rats were reinforced using a PR schedule. During this phase, rats were required to depress the right-side lever an increasing number of times to obtain each subsequent nicotine infusion and/or cue presentation (according to the algorithm in Arnold and Roberts, 1997). Sessions lasted for 2 h or until a rat failed to respond for 20 consecutive minutes. The highest lever depression ratio achieved within 2 h was defined as the ‘break point’. Because of the increasing demand for a single reinforcer and hence the difficulty to achieve the number of infusions acquired during FR1, the break point is thought to measure motivation to work for a reinforcer such as nicotine (eg, Donny et al, 2000). In addition to break point, active lever responding and number of infusions/cue deliveries were recorded as secondary measures of nicotine and cue reinforcement and inactive lever responding provided a measure of nonspecific lever-pressing activity. Incorporating a 2 h time limit during PR sessions produces a steady level of responding over days of nicotine self-administration (Donny et al, 2000) to enable within-subject analysis of intracerebral infusions of α-CTX MII.

α-CTX MII Brain Infusions

Immediately before PR testing, rats received infusions of 0, 1, 5, or 10 pmol per hemisphere α-CTX MII or vehicle (VEH) in the NAc shell or anterior cingulate. Implanted guide cannula assured that delivery of conotoxin was not to brain areas dorsal to the desired target. Infusions were carried out by a micro infusion pump at a rate of 0.5 μl/min through internal cannula (extending 1 mm beyond the guide) attached to a Hamilton syringe by PE 20 tubing (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA). Rats received 2–3 days of sterile saline infusions to assure a stable level of PR responding followed by a Latin square counterbalanced delivery of doses of α-CTX MII and VEH. Infusions were delivered at a rate of 0.5 μl/min and were followed by a 2 min wait period to allow for drug diffusion and to prevent backflow of α-CTX MII through the guide cannula.

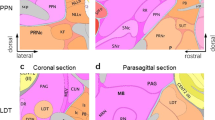

I125-α-CTX MII Brain Infusions

To assess the exposure area of α-CTX MII, a subset of animals received 1 μl infusions of 10 pmol radiolabeled α-CTX MII into the NAc shell and had their brains harvested 2 h after infusion. Following rapid decapitation, brains were removed, fast-frozen in ice-cold isopentane and stored at −80°C. Within 24 h, 40 μm brains sections were collected and mounted using a cryostat. Slides were dehydrated overnight in a vacuum chamber and placed on X-ray film for approximately 30 days. Brain sections were subsequently postfixed in 4% paraformaldehdyde, stained with cresyl violet, scanned, and superimposed with X-ray films for visualization.

Locomotor Testing

A separate group of rats naive to NAc shell infusion underwent locomotor testing to assess whether α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell contribute to locomotor-activating effects of nicotine. Testing was conducted in a white 2′ × 2′ × 1.5′ (L × W × H) Plexiglas chamber. Animal movement was monitored using a video-tracking system (Panasonic WV-BP330 digital camera) and converted into distance traveled using ANY-maze software (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). On days 1 and 2, VEH injections were administered to habituate animals to the experimental procedures described below; on day 2, rats additionally received a VEH infusion into the NAc shell. All infusions took place 15 min before locomotor procedures. On subsequent days, rats received intra-accumbens shell infusions of VEH, 5, and 10 pmol per hemisphere of α-CTX MII, according to a Latin-square counterbalanced design. Before injection, animal chamber activity was measured for 15 min to assess any effects of α-CTX MII infusion on basal locomotor activity. This also provided daily habituation to the apparatus. Animals then received an injection of 0.175 mg/kg, s.c., nicotine and were immediately replaced in the chamber for an additional 35 min of observation.

Statistical Analysis

Within-subject, repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to analyze effects of vehicle and various concentrations of α-CTX MII on dependent measures during PR and locomotor testing. Post hoc t-tests compared results following α-CTX MII infusion to those following infusion of VEH for each brain area studied. p<0.05 was inferred to be significant (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

α-CTX MII-Sensitive nAChRs in the NAc Shell Regulate Motivation for Nicotine and/or Nicotine-Associated Cues

α-CTX MII infusion into the NAc shell reduced PR responding in nicotine-reinforced rats in a dose-dependent manner. There was an effect of concentration of α-CTX MII on break points (F3,33=3.900, p=0.017) number of infusions (F3,33=3.890, p=0.017) and active lever responding (F3,33=3.322, p=0.032) in NIC rats, but no effect on inactive lever responding (p>0.05) suggesting that α-CTX MII affected motivation for either nicotine or nicotine-associated cues without affecting activity in general. Post hoc t-tests revealed that infusion of 5 and 10 pmol per hemisphere of α-CTX MII into the NAc shell significantly decreased break points (t11=1.869, p=0.04; t11=2.295, p=0.020) and number of infusions received (5 pmol, t11=2.127, p=0.03; 10 pmol, t11=3.534, p=0.003) in comparison to test sessions when animals received VEH infusions (Figure 1). These data suggest that α-CTX MII-sensitive receptors in the NAc shell regulate motivation for nicotine and/or nicotine-associated cues.

α-Conotoxin MII (α-CTX MII)-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell regulate motivation for nicotine and/or nicotine-associated cues during a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. (a) Nicotine-reinforced animals (NIC, n=12) showed a concentration-dependent decrease in the number of responses they gave for a single infusion of nicotine and light+tone cues (break point) as well as (b) a decrease in number of nicotine infusions/cue deliveries following infusion of α-CTX MII into the NAc shell. NAc shell infusion of α-CTX MII had no effect on either break points or number of cue deliveries for animals that received light+tone reinforcement unaccompanied by nicotine (CUEonly, n=7). Data are expressed as mean±SEM; *p<0.05 compared to vehicle.

α-CTX MII-Sensitive nAChRs in the NAc Shell do not Regulate Primary Motivation for Cues

In contrast, there was no effect of NAc shell infusion of α-CTX MII on lever pressing maintained by cues in the absence of nicotine (Figure 1). Previous data have shown that stimulus cues can exert its effects as primary reinforcers in the absence of nicotine (Donny et al, 2003) as appeared to be the case for the compound light+tone stimulus used in this study; like NIC animals, CUEonly animals showed approximately 80% active lever responding during acquisition under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement (Supplementary Figure 1) as well as during PR responding (Supplementary Figure 2). There was no effect of NAc shell infusion of α-CTX MII on break point, number of infusions, and active or inactive lever presses (all F's <1.0, p's >0.05). Together with the data presented above, these findings suggest that α-CTX MII-sensitive nAChRs in the NAc shell regulate motivation for nicotine and this does not generalize to non-nicotine rewards. These data further suggest that the concentrations of α-CTX MII infused into the NAc shell did not impair the motor ability of animals as measured by a lack of α-CTX MII-associated changes on lever pressing in CUEonly animals.

α-CTX MII-Sensitive nAChRs in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex do not Regulate Motivation for Nicotine

The anterior cingulate cortex is a brain structure dorsal to the NAc shell that receives projections from VTA DA neurons and contains α6β2*nAChRs. Infusions of α-CTX MII into the anterior cingulate cortex had no effect on responding to nicotine during PR in either NIC or CUEonly animals (Figure 2). There was no effect of anterior cingulate infusion of α-CTX MII on break point, number of nicotine infusions/cue deliveries, active lever pressing, or inactive lever pressing (All F's <1.0, p's >0.05). Together with the findings above, these data suggest that effects of α-CTX MII on motivation for nicotine were specific to the NAc shell.

α-Conotoxin MII (α-CTX MII)-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the anterior cingulate cortex do not appear to regulate motivation for nicotine or associated cues. (a) Infusion of α-CTX MII into the anterior cingulate cortex had no effect on break point, the number of depressions that rats gave for a single delivery of nicotine and cues (NIC, n=7), or cues alone (CUEonly, n=4). (b) Anterior cingulate cortex infusion of α-CTX MII also had no effect on the total number of infusions and/or cues earned by NIC and CUEonly rats.

α-CTX MII Infusions were Local to the NAc Shell

Figure 3 shows that infusions of α-CTX MII were local to the NAc shell and did not diffuse to nearby structures. Guide cannula further prevented α-CTX MII from traveling up the infusion cannula into overlying brain structures.

I125-α-CTX MII (α-conotoxin MII) infusion into the nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell. (a, c) Representative infusions are shown by overlay of X-ray film with coronal sections from an animal that received a 1 μl infusion of 10 pmol I125-α-CTX MII (shown in black) into the NAc shell. (b, d) Nissl-stained coronal sections showing the NAc shell and core of the samples depicted above.

Concentrations of α-CTX MII Sufficient to Reduce Motivation for Nicotine did not Affect Locomotor Activation

Previous studies suggest that α6β2*nAChRs may regulate locomotor-activating effects of nicotine (le Novere et al, 1999; Drenan et al, 2008; Dwoskin et al, 2008). We therefore sought to determine whether concentrations of α-CTX MII infused into the NAc shell that were sufficient to affect motivation for nicotine self-administration were also sufficient to affect nicotine locomotor activation in a subset of animals that had undergone nicotine self-administration. Planned comparisons between VEH–VEH and VEH–NIC indicated that the dose of nicotine used in these studies resulted in locomotor activation as measured by distance traveled: t15=3.873, p=0.002 (Figure 4). There was no effect of intra-accumbens shell infusion of α-CTX MII on distance traveled in an open field during the habituation period (F1,7=1.640, p=0.241) or following nicotine injection (F1,7=0.511, p=0.498). Together with previous data (Le Novere et al, 1996, 1999; Klink et al, 2001; Cui et al, 2003; Drenan et al, 2008; Dwoskin et al, 2008), the current findings suggest that α6β2*nAChRs in areas other than the NAc shell regulate nicotine locomotor activation.

α-Conotoxin MII (α-CTX MII) infusion into the nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell did not depress locomotor activity in an open field. Animals received s.c. injection of 0.175 mg/kg nicotine (by weight of freebase) in 0.9% saline (NIC) or saline vehicle (VEH). Sessions were preceded by intra-accumbens shell infusion of saline vehicle (VEH), 5 pmol, or 10 pmol of the α6β2*nAChR antagonist, α-CTX MII. (a) Planned comparisons between VEH–VEH and VEH–NIC showed a significant increase in distance traveled following nicotine injection (n=8, p=0.002), indicating that the dose of nicotine used in these studies resulted in locomotor activation. Locomotor-activating effects of nicotine were not affected by antagonism of α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell. (b) Intra-accumbens shell infusion of α-CTX MII also had no effect on basal locomotor activity. Data are expressed as mean±SEM; *p<0.05 compared with activity following vehicle infusion and vehicle injection.

DISCUSSION

These data show that α-CTX MII-sensitive nAChRs in the NAc shell are critical for motivation to self-administer nicotine and associated cues. Concentrations of α-CTX MII that are capable of blocking nicotine-stimulated DA release (Kulak et al, 1997; Salminen et al, 2004) were sufficient to attenuate break points and consequently the number of nicotine infusions received during PR testing. This effect was neuroanatomically specific to the NAc shell; similar infusions into the anterior cingulate cortex had no effect on nicotine self-administration during PR. These effects were also specific to nicotine self-administration; there was no effect of α-CTX MII infusion into the NAc shell on lever pressing maintained by light+tone stimuli in the absence of nicotine and no effect on locomotor activity in an open field.

α-CTX MII-associated reductions in nicotine self-administration during PR tests were likely due to blockade of α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell. α-CTX MII antagonizes both α6β2* and α3β2*nAChRs; however, deletion of α6 subunits essentially eliminates striatal I125-α-CTX MII binding (Champtiaux et al, 2002). In contrast, deletion of the α3 subunit has no effect on I125-α-CTX MII binding to dopaminergic neurons (Whiteaker et al, 2002). I125-α-CTX MII binding is also absent in β2 subunit null mutant mice and unaffected by β4 subunit deletion (Salminen et al, 2005), thus, the target of α-CTX MII in the NAc shell appears to be the high-affinity α6β2*nAChRs (for review, see Grady et al, 2007).

These self-administration studies in rats expand on previous data that showed that α6β2*nAChRs regulate acquisition of nicotine self-administration (Pons et al, 2008) to identify the NAc shell as a critical neuroanatomical locus of α6β2*nAChR contributions to nicotine intake. Recent work in mice shows that lentiviral recovery of α6nAChR subunit mRNA in the VTA region of α6nAChR subunit knockout mice is sufficient for initiation of nicotine use as measured by tail-vein self-administration (Pons et al, 2008). The present findings suggest that α6β2*nAChRs may also support maintenance of nicotine use. Recovery of β2nAChR subunit mRNA into the VTA is sufficient for more prolonged intra-VTA self-administration of nicotine (Maskos et al, 2005), but local infusion of nicotine bypasses brain areas outside the VTA, which may also contribute to nicotine use. Recovery of α6 receptor subunit mRNA in the VTA ought to rescue expression of α6β2*nAChRs on neuron terminals in multiple VTA projection regions, including the NAc core and shell, the dorsal striatum, and the anterior cingulate (Mineur et al, 2009). In the present study, α-CTX MII antagonism of nAChRs in the NAc shell, but not the anterior cingulate cortex, greatly attenuated break points during PR testing, suggesting that activation of α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell contributes to motivation to self-administer nicotine. Previous studies have reported that antagonism of NAc β2*nAChRs with dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) did not affect nicotine self-administration under an FR 5 schedule (Corrigall et al, 1994), perhaps due to a broader neuroanatomical target that included the core and shell, or perhaps due to the fixed schedule of reinforcement used in these earlier studies. DHβE blocks all nAChRs that contain a β2subunit. It is possible that antagonism of α4β2*nAChRs and α6β2*nAChRs has opposing effects in the NAc shell as appears to be the case in the VTA. α-CTX MII but not DHβE infusions into the VTA block the reinforcing properties of cues associated with ethanol (Lof et al, 2007). Effects of α-CTX MII and DHβE antagonism on DA release differ across neuroanatomical regions (eg, Grady et al, 2002; Exley and Cragg, 2008; Exley et al, 2008; Perez et al, 2009). Synaptosome preparations suggest that α-CTX MII-sensitive nAChRs are responsible for approximately 30% of nicotine-stimulated DA release at terminals in the striatum of rats (Salminen et al, 2005). Studies using cyclic voltammetry in slice preparation suggest that DHβE and α-CTX MII have similar effects on basal DA release in the NAc (Exley and Cragg, 2008), but these studies did not parse the NAc core and shell. In vitro studies suggest that nicotinic antagonist effects on DA release are also highly dependent on the firing frequency of neurons and prior nicotine exposure (Rice and Cragg, 2004; Zhang and Sulzer, 2004; Exley and Cragg, 2008; Perez et al, 2008). It is not clear how DA neurons would respond to α-CTX MII antagonism in vivo, but the present data suggest that activation of α6β2*nAChRs is necessary for expression of PR responding maintained by nicotine.

NAc shell α6β2*nAChRs may also regulate conditioned rewarding effects of cues associated with nicotine. Habitual smokers are sensitive to the primary rewarding effects of nicotine, as well as to the conditioned reinforcing properties of cues associated with cigarette smoking (Tiffany and Carter, 1998; Caggiula et al, 2001; Robinson and Berridge, 2003); over time, cues associated with nicotine become capable of controlling mesolimblic DA areas associated with nicotine reward (Stein et al, 1998; Schroeder et al, 2001; Due et al, 2002; Volkow et al, 2007). Cues greatly enhance nicotine self-administration in rodents (Caggiula et al, 2001, 2002) and can sustain self-administration and smoking behaviors in the absence of nicotine (Cohen et al, 2005; Donny et al, 2007). Recent data implicate VTA α6β2*nAChRs in regulation of conditioned rewarding effects of light+tone cues associated with ethanol (Lof et al, 2007). Other studies show that rats will press for visual stimulus cues in the absence of other primary reinforcers, suggesting that putative conditioned stimuli can have primary reinforcing value on their own (Donny et al, 2003; Olsen and Winder, 2009) and this behavior is DA mediated (Olsen and Winder, 2009). Rats in the present studies showed greater responding on the active than the inactive lever when reinforced with the light+tone cues independent of nicotine reinforcement. Unlike responding to nicotine and cues, however, responding to cues alone was not attenuated by infusion of α-CTX MII into the NAc shell, indicating that α-CTX MII-sensitive nAChRs in the NAc shell do not regulate the primary reinforcing properties of light and tone cues. These data further suggest that α-CTX MII-associated decreases in responding maintained by nicotine infusion were not due to motor impairments. These data suggest that α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell regulate the primary reinforcing effects of nicotine, the conditioned reinforcing effects of nicotine-paired cues, or perhaps nicotine-associated enhancement of conditioned reward, behaviors shown in previous studies to be regulated by β2*nAChRs (Picciotto et al, 1998; Maskos et al, 2005; Brunzell et al, 2006). In this respect the NAc shell population of α6β2*nAChRs may differ from those in the VTA where α6β2*nAChRs contribute to ethanol and nicotine reward (Pons et al, 2008; Kuzmin et al, 2009), suggesting that α6β2*nAChRs in the VTA may have a more general role in primary reward.

Although α6β2*nAChRs are implicated in the locomotor-stimulating effects of nicotine (le Novere et al, 1999; Drenan et al, 2008; Dwoskin et al, 2008), the results of the present study suggest that nicotine locomotor activation is likely controlled by α6β2*nAChRs in areas other than the NAc shell. Intra-accumbens shell concentrations of α-CTX MII that effectively reduced lever pressing for nicotine were insufficient to affect distance traveled in an open field, showing a disassociation for the role of NAc shell α6β2*nAChRs in nicotine's locomotor activation and reinforcing effects. Pharmacological data suggest that α6β2*nAChR effects on locomotor activity are DA mediated (Drenan et al, 2008). α6β2*nAChRs are among nAChR subtypes on terminals in the accumbens core and shell that regulate DA release and α6β2*nAChRs within the VTA regulate DA neuron excitability (Salminen et al, 2004, 2007; Drenan et al, 2008). Although acute nicotine activation effects are associated with DA release in the NAc shell (Iyaniwura et al, 2001), blockade of accumbens shell α6β2*nAChRs with α-CTX MII did not reverse locomotor-activating effects of nicotine in these studies. Several reports suggest that nicotinic receptors in the VTA control locomotor-activating effects of nicotine (eg, Corrigall et al, 1994; Ferrari et al, 2002) and that elevated DA release in the NAc core, rather than the shell, is critical for DA-mediated locomotor-stimulating effects of nicotine following repeated exposure (Cadoni and Di Chiara, 2000; Boye et al, 2001; Iyaniwura et al, 2001; Kelsey et al, 2009). More work is needed to identify the neuroanatomical loci where α6β2*nAChRs exert their effects on locomotor activity.

In summary, these studies suggest that α-CTX MII-sensitive receptors in the NAc shell regulate motivation for nicotine and/or motivation supported by cues associated with nicotine. These findings expand on previous reports to suggest that α6β2*nAChRs support nicotine self-administration after sustained nicotine use. As both nicotine and cigarette-associated cues are thought to contribute to smoking maintenance and relapse, the present studies identify α6β2*nAChRs in the NAc shell as potential targets for smoking cessation therapy.

References

Arnold JM, Roberts DC (1997). A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 57: 441–447.

Boye SM, Grant RJ, Clarke PB (2001). Disruption of dopaminergic neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens core inhibits the locomotor stimulant effects of nicotine and D-amphetamine in rats. Neuropharmacology 40: 792–805.

Brunzell DH, Chang JR, Schneider B, Olausson P, Taylor JR, Picciotto MR (2006). beta2-Subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are involved in nicotine-induced increases in conditioned reinforcement but not progressive ratio responding for food in C57BL/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 184: 328–338.

Brunzell DH, Picciotto MR (2009). Molecular mechanisms underlying the motivational effects of nicotine. Nebr Symp Motiv 55: 17–30.

Cadoni C, Di Chiara G (2000). Differential changes in accumbens shell and core dopamine in behavioral sensitization to nicotine. Eur J Pharmacol 387: R23–R25.

Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Perkins KA, Evans-Martin FF, Sved AF (2002). Importance of nonpharmacological factors in nicotine self-administration. Physiol Behav 77: 683–687.

Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA et al (2001). Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 70: 515–530.

Cartier GE, Yoshikami D, Gray WR, Luo S, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM (1996). A new alpha-conotoxin which targets alpha3beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 271: 7522–7528.

Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C et al (2003). Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci 23: 7820–7829.

Champtiaux N, Han ZY, Bessis A, Rossi FM, Zoli M, Marubio L et al (2002). Distribution and pharmacology of alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J Neurosci 22: 1208–1217.

Christian MS, Hoberman AM, Johnson MD, Brown WR, Bucci TJ (1998). Effect of dietary optimization on growth, survival, tumor incidences and clinical pathology parameters in CD Sprague–Dawley and Fischer-344 rats: a 104-week study. Drug Chem Toxicol 21: 97–117.

Cohen C, Perrault G, Griebel G, Soubrie P (2005). Nicotine-associated cues maintain nicotine-seeking behavior in rats several weeks after nicotine withdrawal: reversal by the cannabinoid (CB1) receptor antagonist, rimonabant (SR141716). Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 145–155.

Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL (1994). Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 653: 278–284.

Corrigall WA, Franklin KB, Coen KM, Clarke PB (1992). The mesolimbic dopaminergic system is implicated in the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 107: 285–289.

Cui C, Booker TK, Allen RS, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ et al (2003). The beta3 nicotinic receptor subunit: a component of alpha-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate dopamine release and related behaviors. J Neurosci 23: 11045–11053.

Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Rowell PP, Gharib MA, Maldovan V, Booth S et al (2000). Nicotine self-administration in rats: estrous cycle effects, sex differences and nicotinic receptor binding. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 151: 392–405.

Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA et al (2003). Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 169: 68–76.

Donny EC, Houtsmuller E, Stitzer ML (2007). Smoking in the absence of nicotine: behavioral, subjective and physiological effects over 11 days. Addiction 102: 324–334.

Drenan RM, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, McClure-Begley T, McKinney S, Miwa JM et al (2008). In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity alpha 6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron 60: 123–136.

Due DL, Huettel SA, Hall WG, Rubin DC (2002). Activation in mesolimbic and visuospatial neural circuits elicited by smoking cues: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Psychiatry 159: 954–960.

Dwoskin LP, Wooters TE, Sumithran SP, Siripurapu KB, Joyce BM, Lockman PR et al (2008). N,N′-Alkane-diyl-bis-3-picoliniums as nicotinic receptor antagonists: inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine release and hyperactivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326: 563–576.

Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, Cragg SJ (2008). Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 2158–2166.

Exley R, Cragg SJ (2008). Presynaptic nicotinic receptors: a dynamic and diverse cholinergic filter of striatal dopamine neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol 153 (Suppl 1): S283–S297.

Ferrari R, Le Novere N, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP, Zoli M (2002). Acute and long-term changes in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway after systemic or local single nicotine injections. Eur J Neurosci 15: 1810–1818.

Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB et al (2006). Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 296: 47–55.

Grady SR, Murphy KL, Cao J, Marks MJ, McIntosh JM, Collins AC (2002). Characterization of nicotinic agonist-induced [(3)H]dopamine release from synaptosomes prepared from four mouse brain regions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301: 651–660.

Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC et al (2007). The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol 74: 1235–1246.

Iyaniwura TT, Wright AE, Balfour DJ (2001). Evidence that mesoaccumbens dopamine and locomotor responses to nicotine in the rat are influenced by pretreatment dose and strain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 158: 73–79.

Kelsey JE, Gerety LP, Guerriero RM (2009). Electrolytic lesions of the nucleus accumbens core (but not the medial shell) and the basolateral amygdala enhance context-specific locomotor sensitization to nicotine in rats. Behav Neurosci 123: 577–588.

Klink R, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Zoli M, Changeux JP (2001). Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J Neurosci 21: 1452–1463.

Kulak JM, Nguyen TA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM (1997). Alpha-conotoxin MII blocks nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in rat striatal synaptosomes. J Neurosci 17: 5263–5270.

Kuryatov A, Olale F, Cooper J, Choi C, Lindstrom J (2000). Human alpha6 AChR subtypes: subunit composition, assembly, and pharmacological responses. Neuropharmacology 39: 2570–2590.

Kuzmin A, Jerlhag E, Liljequist S, Engel J (2009). Effects of subunit selective nACh receptors on operant ethanol self-administration and relapse-like ethanol-drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 203: 99–108.

Le Novere N, Zoli M, Changeux JP (1996). Neuronal nicotinic receptor alpha 6 subunit mRNA is selectively concentrated in catecholaminergic nuclei of the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci 8: 2428–2439.

le Novere N, Zoli M, Lena C, Ferrari R, Picciotto MR, Merlo-Pich E et al (1999). Involvement of alpha6 nicotinic receptor subunit in nicotine-elicited locomotion, demonstrated by in vivo antisense oligonucleotide infusion. NeuroReport 10: 2497–2501.

Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH (2006). Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 184: 523–539.

Lof E, Olausson P, deBejczy A, Stomberg R, McIntosh JM, Taylor JR et al (2007). Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral tegmental area mediate the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 195: 333–343.

Maskos U, Molles BE, Pons S, Besson M, Guiard BP, Guilloux JP et al (2005). Nicotine reinforcement and cognition restored by targeted expression of nicotinic receptors. Nature 436: 103–107.

McIntosh JM, Azam L, Staheli S, Dowell C, Lindstrom J, Kuryatov A et al (2004). Analogs of alpha-conotoxin MII are selective for alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 65: 944–952.

Mineur YS, Brunzell DH, Grady SR, Lindstrom JM, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ et al (2009). Localized low-level re-expression of high-affinity mesolimbic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors restores nicotine-induced locomotion but not place conditioning. Genes Brain Behav 8: 257–266.

Olsen CM, Winder DG (2009). Operant sensation seeking engages similar neural substrates to operant drug seeking in C57 mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 34: 1685–1694.

Perez XA, Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Quik M (2008). Long-term nicotine treatment differentially regulates striatal alpha6alpha4beta2* and alpha6(nonalpha4)beta2* nAChR expression and function. Mol Pharmacol 74: 844–853.

Perez XA, O'Leary KT, Parameswaran N, McIntosh JM, Quik M (2009). Prominent role of alpha3/alpha6beta2*nAChRs in regulating evoked dopamine release in primate putamen: effect of long-term nicotine treatment. Mol Pharmacol 75: 938–946.

Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM et al (1998). Acetylcholine receptors containing the beta2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature 391: 173–177.

Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM et al (2008). Crucial role of alpha4 and alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci 28: 12318–12327.

Rice ME, Cragg SJ (2004). Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci 7: 583–584.

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (2003). Addiction. Annu Rev Psychol 54: 25–53.

Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA et al (2007). Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 52: 985–994.

Salminen O, Drapeau JA, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Grady SR (2007). Pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. Mol Pharmacol 71: 1563–1571.

Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC et al (2004). Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol 65: 1526–1535.

Salminen O, Whiteaker P, Grady SR, Collins AC, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ (2005). The subunit composition and pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors studied by a novel membrane-binding assay. Neuropharmacology 48: 696–705.

Schroeder BE, Binzak JM, Kelley AE (2001). A common profile of prefrontal cortical activation following exposure to nicotine- or chocolate-associated contextual cues. Neuroscience 105: 535–545.

Stein EA, Pankiewicz J, Harsch HH, Cho JK, Fuller SA, Hoffmann RG et al (1998). Nicotine-induced limbic cortical activation in the human brain: a functional MRI study. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1009–1015.

Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C et al (2004). Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science 306: 1029–1032.

Tiffany ST, Carter BL (1998). Is craving the source of compulsive drug use? J Psychopharmacol 12: 23–30.

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM, Telang F (2007). Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications. Arch Neurol 64: 1575–1579.

Whiteaker P, Peterson CG, Xu W, McIntosh JM, Paylor R, Beaudet AL et al (2002). Involvement of the alpha3 subunit in central nicotinic binding populations. J Neurosci 22: 2522–2529.

WHO (2008). MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic. WHO Perss, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland.

Zhang H, Sulzer D (2004). Frequency-dependent modulation of dopamine release by nicotine. Nat Neurosci 7: 581–582.

Acknowledgements

We thank the AH Lichtman laboratory for generously providing us with use of their tracking equipment for the locomotor studies in this manuscript. We also thank Patrick Taylor, Ayn Buttner, Derrick Bullock, and Yun Ding for their technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants MH53631 and GM48677 to JM McIntosh and NIH grant DA023114 to DH Brunzell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest with any data or original ideas presented in this paper. DH Brunzell has received financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for this work. JMM has served as a consultant and received grant funding from Memory Pharmaceuticals, Targacept, Pfizer, Metabolic Inc., the Ben B and Iris M Margolis Foundation, and the University of Utah Research Foundation for other projects.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunzell, D., Boschen, K., Hendrick, E. et al. α-Conotoxin MII-Sensitive Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Nucleus Accumbens Shell Regulate Progressive Ratio Responding Maintained by Nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacol 35, 665–673 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.171

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.171

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Elucidating the reinforcing effects of nicotine: a tribute to Nadia Chaudhri

Psychopharmacology (2023)

-

Association and cis-mQTL analysis of variants in CHRNA3-A5, CHRNA7, CHRNB2, and CHRNB4 in relation to nicotine dependence in a Chinese Han population

Translational Psychiatry (2018)

-

Nicotine regulates activity of lateral habenula neurons via presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Differential Roles of α6β2* and α4β2* Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors in Nicotine- and Cocaine-Conditioned Reward in Mice

Neuropsychopharmacology (2015)

-

Nicotinic Receptor Contributions to Smoking: Insights from Human Studies and Animal Models

Current Addiction Reports (2015)